In 1987 St John Paul II told the native peoples of America, “The cultural oppression, the injustices, the disruption of your life and your traditional societies must be acknowledged.” On Wednesday, the 28th of October, 2020, this acknowledgement was finally made by the Kumeyaay peoples of San Diego Diocese. For the first time in their long history, a Native American tribe of San Diego spoke out about the atrocities and abuses that they have experienced from the Catholic Church and the State of California. I am grateful to have been able to be a bridge between the Diocese and my Kumeyaay parishoners to make this acknowledgement possible.

It took many years to earn their trust and for them to begin telling me about their past, their families, their traditions, and their relationship with God (Meyahaa). Now they are more open. When I asked two of my parishioners to share their stories at a Diocesan conference held online to air the wrongs done by the Church against Blacks and Indians they said, “yes.” This is their story.

Judy Oyos-Robinson is from the Mesa Grande reservation in the back country of San Diego County. Born of a white mother and an Indian father, who were later separated, she grew up deeply rooted in both her faith and her native traditions. She spoke of the extreme prejudice she experienced in the cities during her formative years. She was called a “wild Indian” by her teacher, and the views taught in the “white man’s history books” were very different from those taught by her father at the reservation back home. The Kumeyaay history is passed down by orally and contains not only the stories but the living spirit of the people.

Their tradition speaks of how the Kumayaay helped Fr Serra build the California Missions. At that time they experienced mistreatment and abuse both from the Church and the State of California. Until very recently the Church has discouraged their native culture, and the first governor of California put a bounty on the head of Indians, saying, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” It is not any wonder therefore, that many Kumayaay hold mixed feelings about newly sainted Junipero Serra. But while acknowledging the wrongs done, Judy’s faith has helped her to overcome these. She says, “I would kiss his hands if he was alive today.”

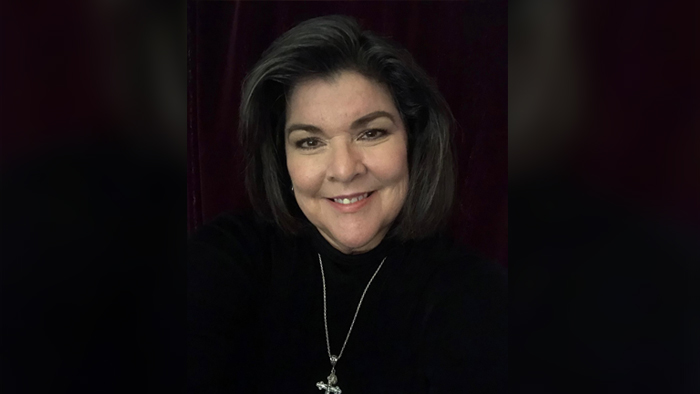

Phyllis Van Wanseele (74) is a member of the Barona Band of Mission Indians. Her father is from the neighboring Viejas Band, but, like all in their tradition, she considers every member of the two reservations her family and calls them by family names—children and grandchildren, brothers and sisters, and aunts and uncles.

In her childhood, three images stand out—shoes, cleanliness and English. Like all the Indian children, she ran about the reservation barefoot. But when the time came for her go away to school her mother said, “Now you must wear shoes and always be clean because the white people think we are dirty.” Her father told her, “Now you must forget our language; to survive you need to learn English.”

Life away from the reservation was very different and adjustment was difficult. She was often insulted and rejected by the other girls. Like them, she wanted to be a “Brownie” but they told her, “You don’t have to join the Brownies, you are already brown.” She felt she didn’t belong and longed for her home on the reservation.

But the feeling of not belonging also extended to the reservation church where the priest’s message was always, “fire and brimstone. It was as if God knew everything you did and only wanted to punish you.” In an effort to grow in her dual identity as an Indian Catholic she read many books exploring the horrendous history of the Kumeyaay, and the atrocities committed by the Spanish, Mexican, Americans and the Catholic Church.

These experiences left her in a state of inner conflict—why remain a Catholic? The Church’s attitude toward her gay son only added to her discouragement. But it was the love and acceptance of Jesus, and the fact that he didn’t discriminate against people because of race, culture, disability or gender, that led her to choose her Native American Catholicity. She says that this choice was vindicated in the canonization of Kateri Tekakwitha in 2012. She says, “Now I am a Catholic and Native American. I have chosen to fuse the two together as both are part of my true identity.”

-Fr. Herman Manuel SVD